There are tons of stories about how now-successful startups took meandering paths and hard-left pivots to find what clicked. Twitter started out as a podcasting platform, Slack was first a live chat for a video game — in our series chronicling founders’ paths to product-market fit, we’ve covered many such twists and turns.

And then there’s the less common tale of the founders who just know exactly what they want to build from the jump and bullishly execute on that vision.

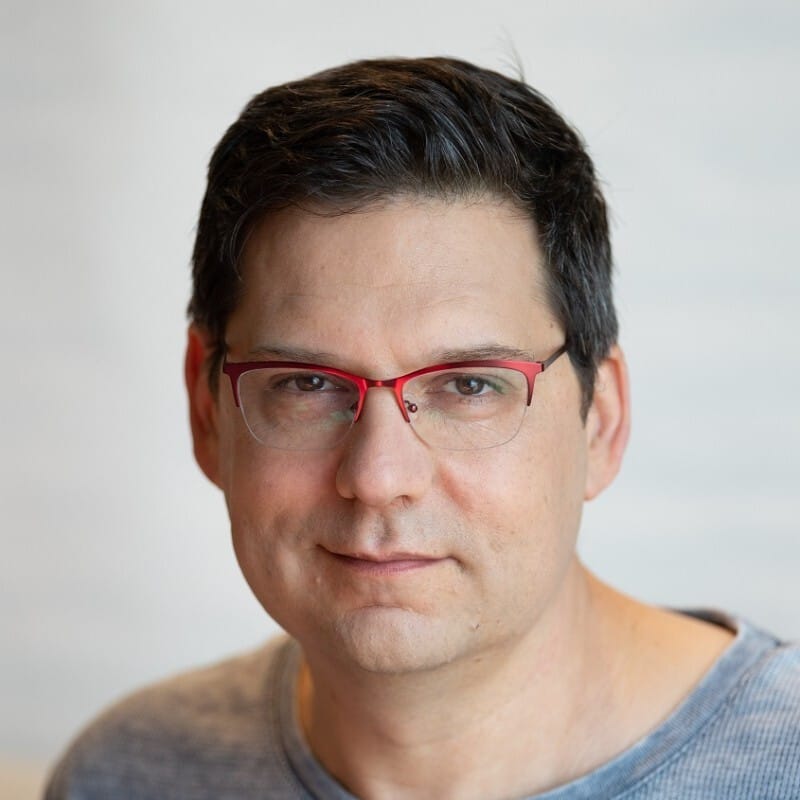

Eilon Reshef has some of that startup clairvoyance. He’s the CPO and co-founder of Gong, an AI-powered platform that helps sales teams better understand customer interactions, born of the conviction that CRMs weren’t telling the full story. After he was pitched the idea for Gong by his co-founder, Amit Bendov, the duo never budged on their vision, even when confronted with quite a bit of doubt — skeptical investors, privacy concerns, an industry married to CRMs and a market that wasn’t yet hot on AI (back in 2015).

Their bet proved to be a good one: Gong now has over 4,000 customers and has raised $584m to date. By Reshef’s account, it only took the company a few months to find initial product-market fit.

But Reshef didn’t just wake up with that intuition one day. A long-time product leader and second-time founder, he started out as an engineer and product architect back in the dot-com era and went on to start ecommerce startup Webcollage, where he served as co-founder and VP of Product for over a decade before he sold it to Answers in 2013.

In this exclusive interview, Reshef reflects on what drove his product instincts and how he brought the vision for Gong to life — and the non-obvious signs Gong had found product-market fit early on, thanks to their design partners. He also shares how he’s balanced his long-term product strategy with customer input as the startup has grown.

VALIDATING THE IDEA

To understand Gong’s journey to become the SaaS powerhouse it is today, let’s start in 2015 — during Reshef’s year-long sabbatical after the sale of Webcollage, when he was hanging out in coffee shops and mulling over his next move.

Dating around for co-founders and problems to solve

Reshef took some time to get to know prospective co-founders and explore different ideas before diving back in for his next venture.

“In all honesty, I was ‘dating’ multiple potential co-founders with multiple ideas. I was on sabbatical, so I had time,” says Reshef.

Then Reshef met Bendov, who had an impressive resume of sales and marketing leadership at tech startups and most recently had served as CEO at Sisense, a business intelligence startup. “Amit had a reputation at the time as being one of the most brilliant and successful entrepreneurs,” says Reshef.

When the two first met up over coffee, Bendov presented an idea he’d been sitting on: a sales problem he’d noticed at Sisense.

“Sisense had just had a really lousy quarter and they were trying to figure out what went wrong. But the CRM showed all good data. Pipelines were moving. Except one thing didn’t happen: Deals didn’t close,” says Reshef. “So what they found out is if they recorded sales conversations to understand what was going on, and if they listened to dozens of them, they got lots of good cues. Amit was like, there’s got to be a more efficient way to do this.”

The idea hinged on the condition that sales conversations take place over video. At the time in 2015, sales orgs used a hybrid model of selling, but Reshef and Bendov agreed that video usage would likely grow. “We didn’t know the pandemic was coming, but we did assume that over time, people were going to be more comfortable using video instead of flying around for meetings,” says Reshef.

Reshef says he knew right away that this DIY sales recording tool could use some help from sleeker software — and AI. “I knew we could figure out how to automate this,” he says.

A tangible problem pulled directly from previous experience and a makeshift process ripe for improvement with new technology — it was a startup match made in heaven. “I liked the idea, I liked the market. So I was definitely interested from the initial meeting,” says Reshef.

Assessing the market

The pair saw a glaring lack of automated tools for sales teams compared to the tech stack available for marketing at the time. “I was looking at the marketing landscape and there were dozens, if not hundreds, of companies that provide campaign automation. There were nowhere near as many for sales. And my thought process was that sales is kind of like marketing. But there weren’t any significant tools outside of a CRM,” says Reshef.

He says he and Bendov found conviction in this idea for a revenue intelligence tool through two things: confidence that other companies must be feeling the same problem, and that AI could solve it.

“First of all, we knew the problem existed at one company, which was Amit’s company. You at least have one potential customer, right?,” says Reshef. “And you can assume that if there’s one SaaS company that has somewhere between $10 and 50 million in sales, there are like-minded companies somewhere out there. And indeed, later on we found them.”

Second, he and Bendov knew AI could root out this blind spot in revenue intelligence, long before anyone was calling it “AI” in the mainstream. “It wasn’t about AI at the time. We didn’t even use the term ‘AI’ because people were scared of AI. So we framed it around sales efficiency,” says Reshef. He and Bendov understood that it was a matter of positioning the value of the tool, rather than leading with the technology itself.

So they pressed on with the idea despite doubts from early investors, who told Reshef and Bendov that CRMs were good enough and worried about the privacy implications of a recording tool.

“Investors weren’t sure if Gong would be in a separate category from CRMs, which was a valid concern. Some were confused about potential overlap with systems for call centers, which were also analyzing calls.” says Reshef.

“And the negative reaction has always been that salespeople aren’t going to want to be recorded,” he explains. “So we focused on the value we’re giving to sellers. The positive side was the dream of AI telling you how to get better and saying, ‘Hey, you’re talking too much during the call.’”

With the suspicion that SaaS companies like Sisense constituted a rough ICP, they knew that the market would be big enough to support a venture-scale company. So they looked for a beachhead within familiar territory and planned to go after customers that were game to be early adopters. They got extremely specific with the criteria of their first ICP:

- B2B software companies

- Based in North America

- Average ticket size between $1,000 – $100,000

- Selling in English

- Used video for sales conversations

“The market was easy to validate. We decided to focus on technology companies because we knew the market, we knew how to approach them and sell to them, and we of course had personal relationships,” says Reshef.

With the idea validated and a beachhead secured, it was time to start building.

BUILDING THE MVP

Before Reshef wrote any code, he and Bendov wanted to whet potential customers’ appetites with a preview of the product. They didn’t even have any mockups — just a good old-fashioned slide deck to communicate the concept of the tool.

“You’ve got to have some sort of a deck when you talk to a customer. You want to show them something, even if it doesn’t exist. So the deck was pretty basic,” he says.

Bendov already had a head start piecing the deck together (“probably 80% of it,” says Reshef) before the two met for their first coffee date. And this proved to be a worthwhile exercise in distilling the company’s value well before the product was born.

You could still use this early pitch deck today if you wanted to sell a very, very basic version of Gong.

So they pitched a couple companies to get them interested in giving the initial product whirl. “Some of the people said, ‘Hey, show it to us when you have it. We like the idea.’ Though some said that and never came back, and were probably just trying to be nice.”

After landing some potential early customers, Reshef and Bendov raised pre-seed money on their own in October 2015 and quickly got to work on an MVP.

Developing the beta

Splitting up functional responsibilities between the pair wasn’t very hard — they fell into a natural setup based on what each had the most experience doing. “I said to Amit, ‘What do you prefer, sales and marketing?’ And Amit said to me, “You want to do product and engineering?’ And that’s how we split it up at first.”

Reshef’s technical background came in handy during the early days. He was a one-man engineering team for the first few months, even though he was a little rusty. It had been years since he’d actually done any coding himself. “Amit said to me, ‘Hey dude, you’re the engineering guy. You have to write something for the company.’ So I thought okay, I’ll download an IDE, open an Amazon account and a cloud account using my Gmail account. So I put together the first prototype myself. I kind of forced myself to remember how to code.”

That first prototype was pretty basic: a screen recording bot, a third-party transcription engine, commenting capabilities and some lightweight AI to analyze seller-to-customer talking ratios.

But Reshef’s bare-bones engineering wasn’t a blocker — in fact, the technical simplicity of the beta was by design. It was the novelty of the recording tool itself that Reshef and Bendov suspected would be most valuable for their first customers. Reshef knew that more sophisticated product features were projects for much further down the road.

That focus on customer satisfaction and demand over efficiency early on (a strategy that tracks with our research into the four levels of PMF) sparked debates with investors. “The idea was to keep it very lean. I even remember one of our investors telling me, ‘You’ve got to have your own speech-to-text engine. I said, ‘Of course, but I’m not going to put it into a beta.’ And he was like, ‘Well, that’s not affordable. You’re going to pay too much. Google charges an arm and a leg. How are you going to figure out the unit economics?’ And I said, ‘I’ll tell you about unit economics when we get to Series B or C. Right now, I want to focus on product-market fit.’”

With the first version of Gong stitched together, Reshef and Bendov put it in front of the people they’d shown the pitch deck to. “We let them play around with the software because I couldn’t scale it. It was just recording one call at a time. So the most you could get is six or so calls recorded per day,” says Reshef.

After that, Reshef brought on a small crew to help build out the early product — friends from his previous company, Webcollage. They helped finalize the first beta by January 2016.

Working with design partners

Reshef is a big advocate for using design partners, no matter if your company is tinkering with an MVP or rolling out dozens of new features. “I’d probably lose an arm before I lose design partners,” says Reshef.

When the team was putting the finishing touches on the beta, they worked closely with 12 design partners as their first batch of users, who were individual sellers working at companies that fell within Gong’s ICP. These design partners would go on to deliver the early signals that Gong had found product-market fit (more on that below).

“Design partners should be people who believe in the product’s value and are willing to invest some time to test it out. They’re aligned with you on how this could change the business and are willing to give you feedback,” says Reshef.

Reshef outlines the two profiles that Gong looks for in design partners:

- The innovator: Someone who believes in the long-term potential of the product, not just what it can do today. They’re maybe a little “over-excited” about using it and the value it can provide. This is who you want in the early stages when you’re first testing your initial hypothesis.

- The programmer: Someone who wants to know what they can get out of the product right now and how they can configure it to their own needs. They’ll tell you if it’s actually working. This is who you want as your company matures and you launch new products and features.

At Gong, design partners aren’t just for the early stage — the company works with many to this day. “We have about 20 to 25 product managers today, and at any given time, each one of them is working with a half dozen to a dozen design partners. That’s quite a bit.”

As for payment, Reshef’s contention is that early startups shouldn’t worry about charging their very first design partners. Instead, he advises founders to focus on finding design partners who fit the “innovator” bill. “In the early stage, I wouldn’t worry about payment as a key thing. There’s always a question of, ‘Can we charge for it?’ And there are many ways to find proxies for value in some form. But they haven’t seen the value yet,” Reshef explains.

EARLY SIGNS OF PRODUCT-MARKET FIT

It didn’t take Reshef and Bendov very long to find traction with their design partners — their idea had proved to be spot-on. “We had this strong hypothesis that just giving people visibility into what’s happening within a sales organization is super important,” says Reshef. “So, we didn’t need to iterate much in order to get product-market fit.”

But that wasn’t exactly obvious at the time. Reshef can more clearly spot the signals that they’d found product-market fit in hindsight.

“We were in the trenches. Amit and I were always looking for what we could improve, which isn’t a bad idea. But then you’re never in celebration mode,” says Reshef.

On that note, he shares a reminder to founders: Don’t forget to celebrate the early wins. It’s easy to only focus on what else you need to do.

So even though Reshef is better able to celebrate these small victories in retrospect, here are the three unexpected signs that Gong had found product-market fit with their 12 design partners:

1: Complaints

The earliest indication that Gong’s first users actually cared about this tool was that they started to feel its absence on sales calls — and complained about it.

“Our design partners started telling us, ‘How come you didn’t record this call?’ Which is ironic because Amit’s vision for Gong was just to record some of the calls and do the analytics from there, and it’ll work the same way. But it turns out sellers and managers were like, ‘I’m relying on this tool to be my eyes and ears and notepad for all of my calls,’” says Reshef.

“Getting so many complaints about our system not recording all calls, which it wasn’t even designed to do, should have given us better indication that it was becoming a critical tool versus just a nice-to-have.”

Criticism is better than people ignoring you, which means they probably don’t need your product. If people start complaining, that’s usually a good sign.

2: Silence

Once Reshef and the team fixed bugs to make sure the tool was recording all calls, their design partners went quiet. This silence that followed meant that they’d gotten what they were asking for — the ability to use the tool for every sales conversation — and carried on quietly using the product.

That’s when the team knew it was time to start charging them.

3: Willingness to pay

Up until this point, all 12 design partners had been using Gong for free. Reshef remembers calling them up and saying, “Hey, beta is over. We’re going to start charging.”

This is where he recognizes the third and final, and perhaps most important, signal that they’d built a product people actually wanted: 11 out of the 12 design partners paid immediately. And the 12th design partner did eventually end up paying — just a year later, when that Gong champion joined a new company.

But instead of celebrating these milestones in the moment, the team dove head-first into growing the company.

SCALING UP

Reshef and Bendov started to really feel the momentum of product-market fit once their design partners started paying. So they hired a few founding SDRs to bring on more customers and within their first year of selling, two years after founding, Gong netted around $2M in ARR — and jumped up to $9M by the second year.

“That was a big thing, moving from two to nine million. I was like okay, this is exploding,” says Reshef.

Balancing strategic and tactical product priorities

As Gong landed more and more customers, Reshef and Bendov’s vision for the product collided with their customers’ reality. They discovered a use case they hadn’t thought of in early product development: Sales managers wanted to use Gong to coach team members.

So one of Gong’s first customer-requested product features in its first year was scorecards, which allows managers to track performance and leave feedback. “Initially we just said, ‘Hey, Gong is going to record your calls.’ And then we added this layer of coaching because that’s the first thing people were looking for. It’s still a very popular use case with Gong,” says Reshef.

“At the same time, this whole notion of where Gong is now, which is this system that semi-autonomously understands what’s going on, helps you forecast and filter out which deals to focus on, which is now possible with GPT — that was Gong-led,” he says.

This was an important learning for Reshef about finding a place for customer input within a founder-led product strategy. Over the years, he’s devised a product roadmap that’s inclusive of strategic and tactical plans — building more revenue intelligence tools with extensive AI capabilities alongside real requests from customers.

I think the strategic roadmap is maybe 80% ‘vision.’ And then the tactical roadmap is probably 80% customer-led.

To translate those product priorities into quarterly planning agendas, Reshef has developed this framework for splitting up engineering resources between the Gong-led vision and customer-driven projects:

- 50% in the core product

- 25% in short-term, tactical projects

- 25% in net-new, strategy-led projects

Expanding toward “product completeness”

Because Reshef and Bendov haven’t strayed far from their day-one strategic vision for Gong, expanding into multi-product meant rolling out tools that pushed the platform closer to the revenue intelligence hub it is today, with more predictive abilities thanks to AI.

“The two SKUs we released after we built our core conversation intelligence product were on our route to what we now call revenue intelligence — an SKU on the forecasting process and an SKU on sales engagement, which is interacting with customers,” he explains.

On the subject of launching these products, Reshef shares a contrarian point of view: He doesn’t actually think of them as new products, but rather steps toward a more complete product.

In the case of those first two SKUs, says Reshef, “We weren’t moving into a brand-new category. So I don’t think we needed to find product-market fit again because at the end of the day, product-market fit is for a category. So for us, it’s more about product completeness,” he says.

These are the questions Reshef poses to determine product completeness:

- Is the core business problem being addressed?

- Can this new offering compete with other players in the market? Can it win a high percentage of deals?

These additional products in Gong’s core category translated into a cross-sell GTM approach. “The first product, Forecast, was intended as a cross-sell motion. So we wanted to get to X percent of Gong customers using it within the first year,” says Reshef.

Gauging customer satisfaction with new products

As for launching products in new categories, Reshef says the team at Gong has held on to a concept pulled from the pages of The Review — the classic survey from Superhuman founder and CEO Rahul Vohra’s approach to assess product-market fit with customers.

“The first thing we launched in a new category was this whole idea of pipeline management. So we asked customers this question that was popularized by Superhuman: ‘How disappointed would you be if we took this away?’ This is more of a product-market fit question which tells us that there’s an early batch of customers who would be very disappointed, and how big that batch is,” explains Reshef.

Vohra’s framework leans on a benchmark from Sean Ellis’ customer development survey to define startups with strong traction, which had all scored at least 40% — a bar Gong cleared easily with its customers. “Our responses were very high, meaning around 80% of the customers we surveyed said they’d be ‘very disappointed,’” says Reshef.

LOOKING FORWARD

Reshef and Bendov have never been scared to stare down the future, just as they did in 2015, betting on AI’s tactical business applications long before consumers got comfy with it.

So what’s next for revenue intelligence? Reshef thinks that sales orgs will keep getting more efficient as AI gets better and better. “Things like updating CRM fields so that the company can analyze them — internally, we call it ‘drudgery.’ Sharing information, writing summaries, creating account handoffs and more — AI should be able to do all this,” says Reshef. “So without the drudgery, salespeople will be left with the good stuff, the fun stuff, which is building relationships, which is what they like to do.”

As Reshef looks ahead to the next 10 years, he shares one final word of wisdom to fellow founders: Find what drives your own conviction and lets you look beyond the horizon. “As a founder, you have to have self-conviction because otherwise you’re not going to start a company. Most people will tell you it’s going to fail, right? Most VCs did not want to invest in Gong in the beginning,” he says.

This article is an edited version of our podcast interview with Reshef on In Depth. For more of Reshef’s insights as a product-focused founder, listen to the full episode.