In the earliest days of building, the founder is the company. Their fingerprints are pressed across every nook and cranny of the business — each decision, hire and product feature. Most early-stage investors will tell you (us included) that the strength of the founding team is the single most important factor in whether a business sinks or swims early on.

While some might tout that it’s the tangible stats here that matter most (like the founder’s previous experiences), Clay co-founder Kareem Amin believes that it goes many layers deeper.

“Your personality plays a major role in your success because building a company exaggerates all of your traits. You’re influencing how things get done — for better or for worse. So you need to be able to clearly see what is going on in the organization and how your personality is being amplified through this process,” Amin says.

He sketches out an example: “You might be someone who pays a lot of attention to detail — which is great. You’re being super careful, you’re producing excellent work. But you’re also slowing down the team and the decision-making, and you might not be aware that it’s happening.”

This heightened awareness is no doubt the product of Amin’s experiences as a second-time founder, giving him more foresight this time around into how founder psychology can be a buoy or an anchor. (His previous company, Frame, was acquired by Sailthru in 2012.)

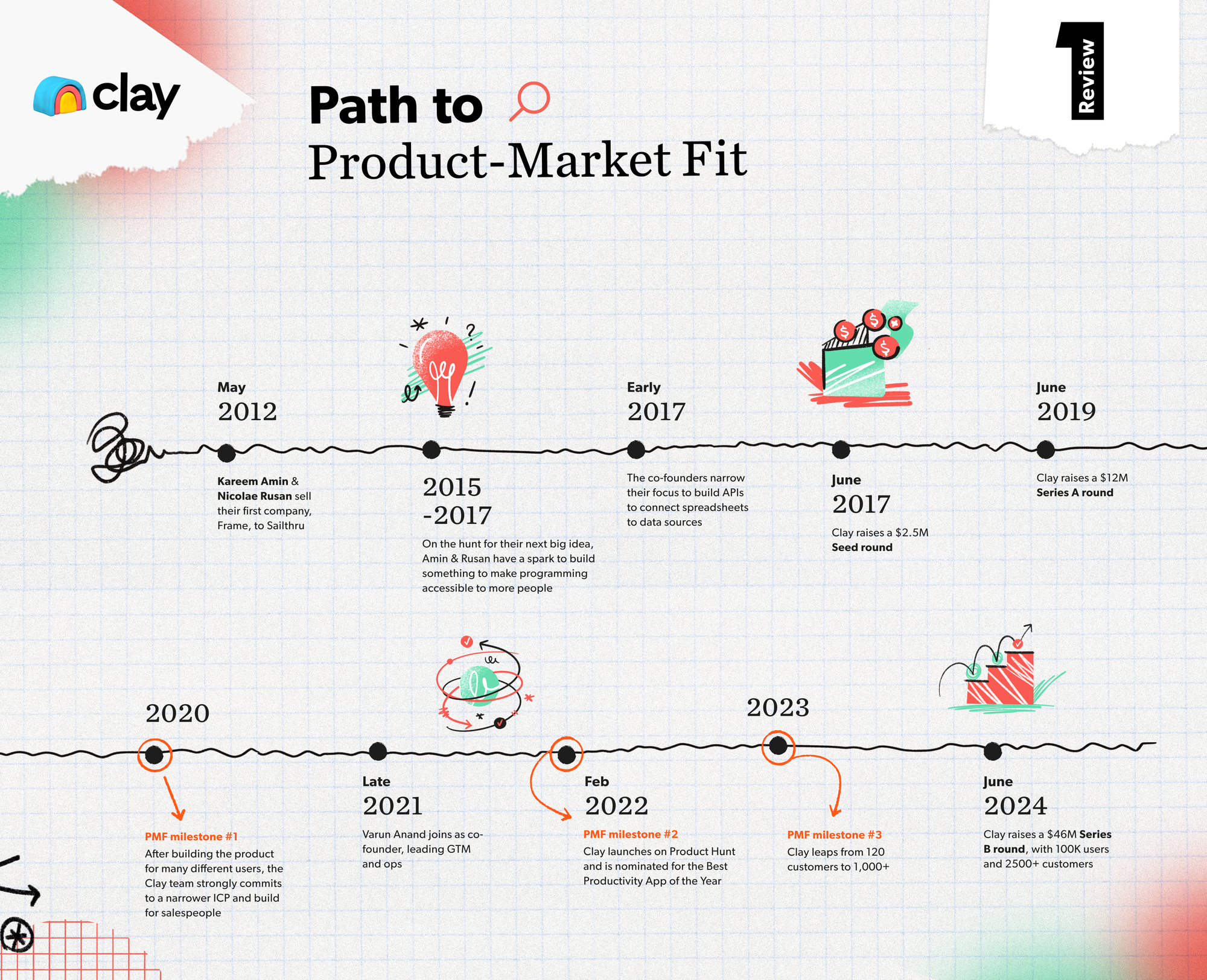

As investors in Clay since the very first round, we’ve seen Amin’s thoughtful approach up close. The company’s growth story is what we like to describe as a “slow bake.” Today, Clay helps growth marketers and rev-ops teams enrich their data, automate personalized outreach, and implement any go-to-market idea — but the journey to getting to that polished positioning was a longer one.

Founded in 2017, the Clay team spent six years quietly plugging away before experiencing an explosion of customer and revenue growth. (To underscore just how meteoric the rise has been, the startup was still close to $0 in revenue as recently as spring 2022.) If you fast forward over the years of wandering, the past 18 months look like a classic “overnight success” story. Today, the company shared it has passed 100K users, nabbed 2500+ customers (including Anthropic, Intercom, Notion, Vanta, and Verkada), and raised a $46M Series B round.

In this exclusive interview, Amin unpacks the thinking that has powered Clay’s tremendous progress, from narrowing in on an ICP, to cultivating a strong community and developing the muscle of product discipline. But perhaps most uniquely, he also candidly shares how his own psychology ebbed and flowed with the peaks and valleys of the business, offering up helpful pointers to fellow founders who are interested in examining their own growth paths more closely.Let’s rewind to 2017.

FINDING AN IDEA:

The idea for Clay stemmed from an abstract desire: to make the power of programming accessible to more people. At the time, collaborative software tooling like Figma, InVision and Miro were capturing attention, but Amin and his co-founder, Nicolae Rusan, wanted to leap one step ahead.

“We were thinking about what the next stage might look like. Specifically, we wanted to see how these APIs and SaaS tools on the internet could help people work better. So that’s where we started exploring,” says Amin.

The first idea was to rebuild the terminal — the 1970s emulator of a computer — which would let companies pipe data from one software tool to another. But they quickly realized that a modern terminal would just help developers move faster, not addressing their desire to give the power of programming to more people.

Then the co-founders started thinking about the world’s most popular programming environment: the spreadsheet. “You’re working with data, except it’s not connected to any of the data sources on the internet. What would it look like if we built APIs into a spreadsheet?” he says. “The same way you have higher order programming languages like Python that look more like English, what if a database understood more categories than just text or number? Like a LinkedIn profile, or a Linear ticket, or a HubSpot URL? What if the database knew what you were putting into it and then could get you more information?”

In practice, the early product scraped dozens of databases to pull information directly into a spreadsheet. “Even in the earliest version, we felt this sense of magic. It’s a spreadsheet where, suddenly, data pops up in a cell from somewhere else on the internet,” says Amin. With an initial version built, his co-founder took point on prospecting. “I was skeptical and resistant at first to narrowing it down to prospecting. We didn’t know much about outbound outreach, but Nicolae decided to try it out. It ended up resonating with early customers — but also showed us just how difficult doing our own outbound was.”

IDENTIFYING THE ICP: DIGGING DEEP INTO THE DEBATE BETWEEN HORIZONTAL VS. VERTICAL

But Clay’s co-founders ran into a bit of a conundrum. The problem wasn’t that they didn’t have a market to target — it was that they had too many potential ICPs to pursue.

Recruiters told Amin how useful their product was for finding candidates. Salespeople wanted to use the platform for their inbound and outbound efforts. Front-end engineers could use the spreadsheet as a low-code backend. They even had a customer who was using Clay to transform and send data to their accounting software.

This may sound like a PMF goldmine. But the wide footprint of the product ended up working against the business in the early years. While some horizontal products (like Airtable or Notion) are able to carve out a path where they can be picked up by all sorts of different users, Clay waffled between staying horizontal and going vertical by picking a specific customer.

This experience taught Amin that when it comes to finding product-market fit, getting to the right positioning is often more challenging than getting to the product itself. “This is a common path — a founder starts by thinking a product is cool and then they have to narrow down the customer and the use case, start to tell the story in a cohesive, coherent way, and then the market gets it. The flow isn’t always linear; often it’s very iterative and messy and that’s entirely normal,” he says.

To dig deeper on Clay’s messy flow, Amin shares four more specific flavors of the ICP challenges the team faced early on.

The dangers of not picking when you go wide:

One signal that their approach wasn’t working? The initial spark often died off quickly. “People would feel excited by the possibilities the product opened. But they weren’t always going back and using it the next day,” says Amin. “So actually we had a lot of, ‘Wow, this is so powerful!’ and then no usage, or inconsistent usage.”

Another issue was the wide range of use cases. “We had a bunch of initial customers, but they were all doing very wildly different things. One company actually sent me their code base because they wanted to send all of their data to NetSuite, but they didn’t have time to do it, so they asked us to reverse engineer it,” says Amin.

“It was in the same general sphere of doing some data transformation in a no-code way, but it had nothing to do with sales or recruiting. We just had this running in the background for a long time. They were paying us. But suddenly our servers would go down and we were like, ‘What’s going on?’ And it was just this one company sending a bunch of data to us that needed to get transformed and sent to NetSuite. We had a customer, but it was the wrong customer.”

Often it’s not that you don’t know who the customer is, it’s that you’re not picking — you haven’t committed to one hypothesis over the other. That’s what creates the confusion about what the product is, what the feature set looks like, and what the language that you use in the product even is.

The costs of malleability:

“When you’re an early startup team, one of your strengths is that you’re malleable. A prospect can say, ‘Oh, could you guys do this?’, or ‘Are you guys this?’ And then you can become that, quite easily. What I’ve learned is that you have to know when to be malleable,” says Amin.

“It’s almost like there are two distinct phases. You can be malleable when you’re defining what the product is, but once you’ve taken a pass at that, you need to harden it when you try to go out to market. You can’t be changing the value prop or even the product itself from meeting to meeting. We were being too malleable when we were trying to sell Clay early on, which made it even harder to separate the signal from the noise.”

Malleability is a startup’s greatest weapon — but like all strengths, it’s a double-edged sword.

The claustrophobia of commitment:

It wasn’t that the Clay team set out to have such a wide breadth of users. The problem was the inherent tension between flexibility and focus.

“Maybe three and a half years into building Clay, we were pretty focused on salespeople. But we hadn’t committed to that ICP in a way that showed in the product — like how we prioritized new features, or changed the language on the website,” he says.

This fear of commitment, Amin notes, isn’t uncommon for founders. “When you narrow the scope, it feels claustrophobic. Why are we doing something that’s smaller when we could be doing something bigger? Eventually, we realized that by narrowing down our scope, we were actually increasing our value,” he says.

This was an area for personal introspection, Amin realized in hindsight. “There was something in my psychology that made me feel like, ‘Oh, we could do anything.’ That was the lure of the horizontal product. And that wasn’t an obvious thing until I really dug in. That’s when I realized, ‘Oh, I feel constrained.’ And that now we can’t do these other things because we’re doing this,” he says.

I had to teach myself that just because we’re closing other avenues for now doesn’t mean that we won’t get back to them later. It was also helpful to give myself the reward of recognizing that people were loving the product and using it — even if it was more narrowly. That was worth more than the constraint.

For Amin, this work all starts with self-awareness: “You have to kind of understand how you work in order to navigate the subtleties of all the decisions that you have to make every day,” he says.

There are many ways to cultivate self-awareness, and Amin says founders have to choose the tools that feel right for them. His preferred tools are meditation and a type of therapy called Internal Family Systems (IFS), which involves interacting with yourself from the perspective of your multiple sub-personalities. “So, for instance, if you’re feeling frustrated about something, you may have one part of yourself that wants instant gratification. And another part that wants to wait and be patient. How do you hear each part of yourself clearly and then integrate them? This type of therapy is a way to introspect deeply and understand your motivations,” he says.

“It’s different from coaching because it is a way to introspect deeply and to really understand your motivations. Then you come back up to see how that affects how you go to work and what you’re trying to do. And once I was able to get more insight into that, I had more clarity into how to operationalize that — to make decisions that are more focused, for example,” says Amin.

“You hear a lot of advice to stay focused, but what is focus? Some people think you work on one task in the morning and then flip over to something else in the afternoon. For me, I learned that focus has to mean I don’t even think about anything else. If I start to imagine this other world of possibility, I’m not focused. If I let myself think, ‘I’ll work on this new idea on nights and weekends,’ I’m lying to myself about how focused I am.”

@firstroundcapital What does it mean to be focused as a founder? #startup #founderlife #pmf

An excerpt from our episode with Amin on the In Depth podcast

The “spiral”:

Part of what made it difficult to commit and stay focused was a startup phenomenon Amin refers to as “the spiral.” “We would make a decision to target salespeople. Then we would get sidetracked, pursue another type of user, and then we’d come back to the same spot. And we’d realize, ‘Oh, this is why we made that decision in the first place,’ and then we’d commit to it again. It took a couple of turns,” says Amin.

This is a state that probably feels familiar to most early-stage founders. “One of our customers would say something that would seem really exciting and doable — just slightly off from what we were doing. But we would attempt to go for it to get that customer,” he says.

“Even though we were focused on sales, all these different possibilities continued to emerge within that. We’d commit to talking to salespeople about outbound, but then they would tell us, ‘Well, we’re also doing this inbound thing where a lot of customers are coming to us and they need enrichment.’ At the time, we were focused on just the aggregation of data, but we thought, ‘Oh, maybe we should do that,’” says Amin.

“But then folks would be like, ‘Well, do you have an API? We don’t need the spreadsheet interface for that.’ So we thought, ‘Maybe we should change the product, maybe it needs to look like a graph.’ But when we eventually built an auto-enrichment feature, then people started saying, ‘Well, actually we like this. What if I used this as my CRM?’ And so there was a moment where we considered that path, too.”

How you position — or fail to position — the product shapes all the product features that you build, in addition to shaping people’s view of you.

All of this would send the team into an even deeper spiral over whether outbound was the right wedge. “We would go back and forth between inbound and outbound. One reason to do outbound is that every B2B company needs outbound, but another reason not to do outbound is that it’s quite complex. It’s a fat long tail, and it’s also seemingly a saturated market,” he says.

Sometimes a spiral would leave the realm of sales entirely. “Every once in a while, someone would say something like, ‘Well, I’m a recruiter but I could use this.’ And then we’d rationalize to ourselves that, ‘Well, recruiting is very much just sales. So it’s not really losing focus if we target recruiters, is it?’” says Amin.

The way out of the spiral? Fully committing to the ICP of outbound sales and only selling the same product each time — for real. “It wasn’t so much that I was 100% sure that outbound was the right call, although it was a faster starting point because all companies need it, versus typically only bigger companies needing inbound support, ” says Amin. “It was more that I realized we need to pick one thing at a time, test it out clearly, and then make sure that it aligned with our larger goals — to get a lot of customers that can come in, self-serve and give us feedback that we can react to quickly. That’s when we’d earn the right to execute on the more expansive parts of our mission.”

This is the line of reasoning that helped us climb our way out of the use case spiral: How do we get customers as quickly as possible, so that we can learn as fast as possible, so that we can improve as quickly as possible?

While this period may seem like a never ending loop from the outside, Amin emphasizes the learning was still valuable. “It wasn’t a complete circle. We would arrive at the same place, but we had more information. Obviously we could have done that faster,” he says.

But it can be difficult to recognize the need to extricate yourself once you’re deep into the spiral. Amin returns to examining founder psychology again. “It took hitting the wall a couple of times before I finally recognized that we were not moving as fast as we could be and we were not achieving the milestones as quickly as I wanted to. I was frustrated with myself and felt that I can and should do better,” he says.

Everything in life is a spiral, really. You come back to the same place, but with a new perspective that enables you to see it differently.

“These feelings can manifest in other ways too, such as avoidance. Whenever I identify these patterns in emotions, the first step is to forgive myself and just be kind to myself. Then I try to dig deeper into the root cause,” says Amin.

He suggests founders also apply a wider team lens here. “It was actually less specifically my personality and more a combination of our personalities. Me, my co-founder and the team, we like building things. And so we would see the opportunities, we’d get sidetracked, and we’d overestimate how much we could do,” says Amin.

“In truth, we were a very productive team and we thought that we could build more than we could. Eventually we realized that we needed to understand the total cost of ownership. Yes, we could build something quickly, but then who was going to sell it? Who was going to educate customers about it? Who’s going to iterate on that feature multiple times until it gets really great? That’s what it takes to get to product-market fit.”

Getting there required a personal shift. “It took me a lot of work to shift my attention and perspective to say, ‘Okay, the vision part is not the problem. Our ambition is large. What we’re missing is what are we doing today? And tomorrow?’”

Like many startups, we eventually realized that we were ahead of the market in terms of what we thought the future should look like. But where we were weaker was in being able to say, “What do we need right now to move the needle tomorrow?” The lofty vision was overtaking what we needed in the present.

BUILDING OUT THE PRODUCT:

So the Clay team decided to focus on outbound salespeople as their ICP. To ensure this wasn’t just another false start, they found ways to hold themselves accountable to this narrower purview. According to Amin, this meant:

- Cutting features that weren’t relevant for Clay’s ICP

- Removing any marketing language that wasn’t tailored to salespeople

- Updating all internal documentation across the organization

- Educating the team on this change and making sure everyone was moving in the same direction (which turned out to be hard and contentious in practice)

It took time, but the team eventually saw the payoff of narrowing their focus. “We just needed to internalize what momentum felt like. For instance, we would get a customer who wanted a feature. Then the next customer would want the exact same feature. Then we would build that feature, and the customers would be happy,” he says.

“And then we would hire another engineer because we would get more customers. It was about thinking in these loops instead of thinking in terms of what the product should look like or what features we should build.”

We had to figure out how to feed the process rather than feed the product.

Here were two techniques Amin leaned on to help the Clay team do just that:

Lean into counterintuitive product principles

Many founders say that they start their companies with a thesis in mind, but for Amin, it’s more of an intuition. “Thesis implies more information than I think most people have when they start,” he says.

To ensure you can operationalize your intuition, Amin recommends trying to codify it into a set of product principles in the early days. Establishing these principles, Amin says, gave them a clear direction for their strategy, product features, and other important company-related decisions. He shares the two that power Clay:

- 1). We’re going to aggregate every data source in the world.

- 2). We’re going to be the most flexible tool in the world.

The move to integrate with every single data source instead of creating their own exclusive data source wasn’t exactly intuitive. “It’s almost an a priori way to think about the world. We thought it made sense to use as many data sources as possible to get the information you want,” he says. “For example, maybe there’s a data point of if a company has an office in South Asia. Maybe that’s not relevant to every company so it’s not worth creating it for some data providers, but it’s relevant to this person who’s doing prospecting, so including more streams is helpful.”

Flexibility may seem like a simplistic product principle, but it was also a counterintuitive approach. “It’s at odds with the way the world works right now,” says Amin. “Most tools choose to build by trying to be as easy to use as possible — you aim to shorten the time to value. You come in, you press one button, you’ve got all your leads and you can start sending outbound messages.”

But for the Clay team, flexibility came first — even if that meant the product wasn’t quite so approachable for folks outside of the power user. “When flexibility conflicts with ease of use, we prioritize flexibility first. Once we make something flexible, we then start to think, okay, what is the easiest way to use this?”

Don’t mask PMF with new features

“Once you can clearly articulate your strategy in terms of a couple of principles, the next task is to apply this methodically. Take an idea that you have to market and really push it to the maximum to see if you’ve actually built something worthwhile,” says Amin.

“That means pick the actual customer that you’re talking to, make sure that they have the same title or at least the same jobs to be done, and then really try to sell it to them — without manufacturing new features.”

There’s a tendency when you’re early to be like, “We’re just missing this one thing…” That actually masks the signs of PMF. When the need is large enough, people will buy your product and wait for you to build the rest of the features. That’s actually the main indicator that you have a product that’s worthwhile.

Amin found it helpful to instill serious discipline here. “I told the team that once we agree to something and it’s in our sprint planning, nothing will shift it. If you’re walking to work and you happen to have a new idea, throw it away. We think of ideas during our planning, and then we commit to it unless the data changes. And often the data doesn’t change actually,” says Amin.

“Your mood is usually what changes. The information hasn’t changed. You just feel differently about it. You get excited about something else in the middle of the sprint and start doing that, saying, ‘Well, a customer told us that this feature is going to be great, so it must be important,” Amin says. “Shifting to a more disciplined approach where we committed, executed, and then committed again was critical for Clay. We left space, obviously, for ad hoc things that happened during the week. But we always made sure that the thing we committed to got done.”

This decision to commit is ultimately what led to Clay’s success. “It was actually by cutting off all of the different ways that we supported customers that we saw huge growth,” says Amin.

This focus also allowed the Clay team to build a robust community. Since they were focusing on one narrower ICP, rather than a huge swath of different folks with vastly different needs, Amin had a hunch that their customers might benefit from being put in the same place to share ideas, best practices, and questions with each other.

So they started a Slack group and put all their customers in one channel. It was a bit of an unconventional call — Slack would be the only place where customers could get support from the Clay team. “Before that, you would email us or chat like most startups. But we pushed all of our customers into the same channel.” His hunch turned out to be correct. The community, which started with around 200 people, has grown to 11K+ people today.

The momentum created in this channel shouldn’t be underestimated. “It’s like arriving early to a concert. No one else is there. But then five or 10 people trickle in, and then it escalates,” says Amin. “We quickly built some momentum by bringing the same type of people into the venue and letting them see that, when they come in, they’re seen. They’re like, ‘Oh yeah, I recognize myself in the group that’s here.’”

As an added bonus, the Slack channel turned into a channel for quick hits of feedback for the Clay team. “It was exciting when the team shipped something and you immediately saw instant feedback. You can only do so much to motivate your team without them seeing results,” says Amin.

Reading this, it might be tempting to copy-paste this growth idea for your own company. But Amin warns that there’s no one right approach and that these decisions require thoughtfulness. “There are many, many different approaches and you need to carefully consider whether your strategy is aligned with your execution,” he says.

“For us, the strategy was to target growth people, operations folks and really clever SDRs who are trying all these different techniques and want to share and talk about them. Putting them all in the same place provided value for them above and beyond what the tool does itself. And that’s why it made sense for us to pursue a community strategy,” he says.

“For other B2B founders, the question is how to align your execution to what’s unique about your business? If real-time information and instant responses are important to your product, web chat support probably makes more sense.”

Designing the experience of your customer and making sure it aligns with your product is actually the path to product-market fit — rather than some generalized thinking like, “Here’s how X company did it and this will unlock PMF for me too.”

GAINING TRACTION:

When Clay eventually found product-market fit, Amin says that there were three signals that told him the company had struck gold:

- 1). They started seeing Clay evangelists. “We started seeing people call themselves Clay experts and try to help other people get set up on Clay. There are dozens of Claygencies — agencies that specialize in implementing Clay for customers — some of which have a run rate of over $2M/year, which is wild,” says Amin.

- 2). People were taking Clay with them to new jobs. “We also started seeing people leave their jobs and bring Clay to their new companies.” This created organic momentum by exposing new teams and organizations to the product.

- 3). They were overwhelmed by feature requests. “Sometimes we would ship a bug and then a customer would immediately flag it,” says Amin. This might seem like a misfire — but it was actually a positive indicator. “This is in many ways a good thing because it means that they care and are using Clay. So once those things started to happen, it was clear that we were being pulled along and that a lot of our theses were right.”

“A lot of finding product-market fit is about whether you understand not just is it working? But do we understand why it’s working?” Getting to this point though, says Amin, wasn’t the result of a tightly controlled process. Instead, he recommends approaching it more organically.

I tell my team that we’re not engineers, we’re more like gardeners. We plant something in the soil, but we don’t control which direction it grows in. If it grows to the left, we also grow to the left and try to nurture it and feed it the best that we can. And then we see what it becomes.

LOOKING FORWARD (AND INWARD)

As for Amin’s longer term vision? “We are a creative tool for growth. So with Clay, you should be able to translate any idea that you have for growing your company to reality instantly. I want to be able to turn outbound into a data-driven experimentation platform where you can ask questions like: Who exactly is my ICP? How do I know that they’re my ICP? Who are the people that we should message and what should we say and when? With Clay, I want people to be able to run these GTM experiments almost like a scientist.”

It’s not just Clay that Amin has big plans for though. He doesn’t intend to stop growing as a founder, and a human. Which brings us to Amin’s final founder psychology tip — decouple the wells of personal and professional fulfillment:

“In the beginning, I put a lot of pressure on myself with Clay because I wanted it to be both successful and personally fulfilling. As a founder, your company can become your art project, the thing that you want to be actualized through,” he says. “But this actually decreased the quality of my decision-making because I would get caught in that same spiral of trying to figure out the biggest, most high-impact thing we could possibly do long-term, instead of what is actually useful right now,” he says.

“Now I’ve shifted my mindset. I’ve removed the psychological pressure — it doesn’t have to be the biggest thing, it just has to be what other people think is useful. That enables me to find meaning in the micro-moments — like when a customer is excited and tells me they were able to do something that they couldn’t have done before Clay — and that has actually helped me make better decisions as a founder.”

Read more details on Clay’s next chapter of growth here.

This article is a lightly edited version of our podcast interview with Amin on In Depth. For more tactics on how to build vertical, narrow down your ICP and insights on founder psychology, listen here.